Treasures of ancient Egypt, linguistic gymnastics, Anglo-Franco rivalry

The British Museum's latest exhibition on hieroglyphs has it all - except some honesty about how it happens to have so many Egyptian objects.

It seems fitting to open this newsletter with the Big Bad of the museum scene. The lightning rod for the artefact-related skirmishes of the current culture war; the bastion of Enlightenment knowledge-building; the home of something close to 8 million objects, the vast majority of which are not from the country in which it stands. It could only be the British Museum. Icon of Empire, it squats like an enormous stone toad amongst the genteel Georgian squares of Bloomsbury, aping the temples of the ancient world whilst holding many of their treasures within.

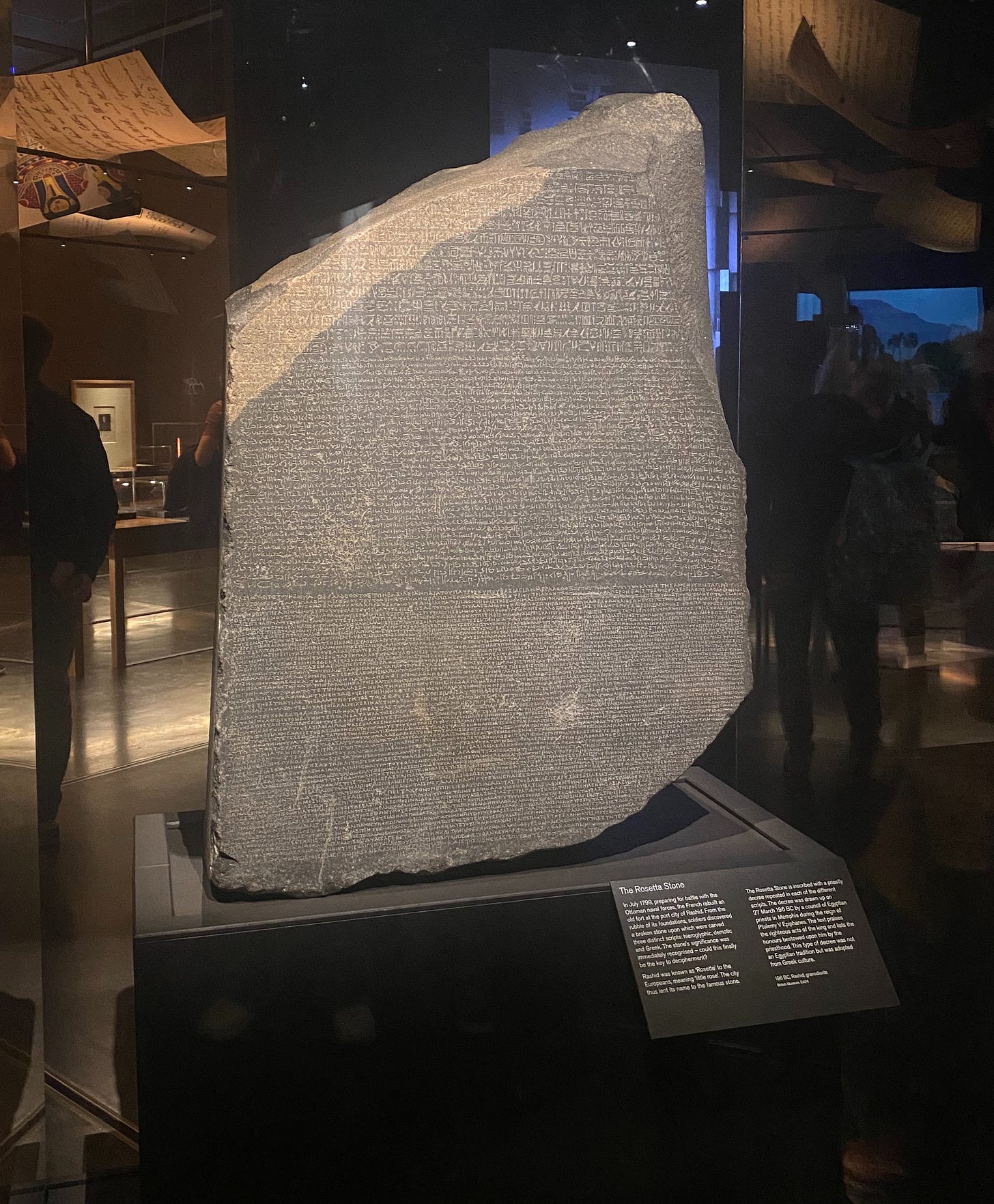

One of these great treasures is the Rosetta Stone – a jagged lump of grey and pink granodiorite which was once part of a stela, bearing a priestly decree from 196BC affirming the royal cult of Ptolemy V, the 13 year old Pharaoh of Egypt. It was donated to the British Museum in 1802 by George III, King of the United Kingdom, after the British army relieved it from the French during the French Revolutionary wars; they, in turn, had uncovered it three years earlier, whilst digging foundations in the city of Rashid in the Nile Delta (where the stone gets its name). Since then, the Rosetta Stone has spent 220 years on display, except for a brief stint underground during WWI, when it was kept in the Postal Tube Railway to protect it from bombing.

Of course, the Rosetta Stone is not just important because it’s a stone, or even because of its inscription (much as we might be fascinated to learn that the Memphis temple supported young Pharaoh Ptolemy). It’s the linguistic possibility captured by the marks carefully cut into rock: three blocks of Greek, Demotic, and Hieroglyphic. The key to cracking the code to 3000 years of human history.

This is the focus of Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt. Charting the path to decipherment through a fascinating array of objects, it’s a slick exhibition with some dramatic flair and impressive technical detail. Putting aside that it was sponsored by bp – a match made in PR heaven/hell – it’s an exhibition that was easy to love, especially for someone who as a nine year old watched Discovery Channel documentaries about the pyramids instead of Tracy Beaker. For anyone, though, seeing artefacts crafted by artisans thousands of years ago will never be anything short of incredible.

The linguistics angle gave it a slightly different edge to that of an exhibition arranged around a singular theme, such as love or death. On the one hand, it gave the curators the opportunity to show the intricacy of hieroglyphics, as well as the clever connections made by scholars when decoding them. A superb example of this was the clear diagram laying out how French philologist Jean-François Champollion compared the names of Cleopatra and Ptolemy to generate matching vowel and consonant sounds, suggesting that the language was both spoken and written.

There was also an appreciation for the materiality of written language, not simply in the massive effort it must have taken to chisel hieroglyphs into stone, but also in the careful painted reproductions of friezes for use by translators, the pages and pages of ink and paper used to painstakingly translate words and phrases, the plaster casts of giant temple walls. A great mass of material needed to manifest the intangible into the tangible, flattening time from 3000 years to the speed of light.

Beneath the impressive staging of awe-inspiring relics was a constant appreciation for the power of the written language to obfuscate and illuminate in equal measure. Never explicitly stated, but always running just under the surface and occasionally coming close to breaching it, was the sense of trust we have in writing, regardless of how pliable it may actually be. Occasionally, that trust was disrupted – but only when we, as an ‘enlightened’ observer in the 21st Century, were in on the apparent lie.

There were a few examples of this. At the start of the exhibition, when documenting the attempts of early modern European scholars to make sense of hieroglyphs, the curators noted a couple of problems. Translations would often be made up to fill gaps in knowledge or to add an air of mysticism. Conversely, ‘authentic’ examples of hieroglyphs also turned out to be elaborate fakes, carved to look like the real thing but reading as gibberish to an ancient Egyptian.

Even when the mystery of the hieroglyphs was unlocked, omissions caused trouble. A massive limestone king-list on display, created in 1250BC, celebrates the predecessors of Ramesses II and Sety I and in doing so legitimises their reign. However, according to the British Museum’s description, the king-list does not mention various leaders – in particular, dynasties considered heretical and women:

The middle row names kings from Senwosret II (Twelfth Dynasty) to Ramesses II, but omits Sebekneferu, the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty (a woman), all the kings of the Second Intermediate Period, the female pharaoh Hatshepsut, and the Eighteenth Dynasty monarchs between Amenhotep III and Horemheb (the Amarna Period).

Deliberately eliminating people who do not fit into the ideal of ancient Egyptian kingship is indicative of the way written language not only communicates the way people thought, it is also part of the apparatus that shapes the society they lived in. To have this object in the exhibition is a stark reminder of the ways words can be wielded to represent and enforce a powerful institution’s point of view.

There is some irony, then, in the little things missing from the Hieroglyph exhibition text. The names of the curators, for a start. It’s written in a voice of God style: the British Museum is the authority, the curatorial team subsumed into the institution. There’s a narrative, sure, but it’s not tainted by anything as gauche as opinion or even light questioning. A viewer is expected to take everything written as irrefutable.

Well – not everything. Some are presented as quotations, like this quote from Dr. Okasha El Daly, Egyptologist and Head of Acquisitions for Qatar University Press: “It is quite clear that the study by medieval Egyptians and Arabs of ancient Egypt, its language, religion, monuments and general history, flourished long before the earliest European Renaissance contact.”

Ostensibly, this is an attempt by the museum to combat Eurocentrism and challenge its audience’s potential preconceived notions about scholarship (preconceived notions produced by the British Museum, but don’t mention that). But it’s juxtaposed with a description by the museum, which informs us that “Arab scholars saw ancient Egyptians as masters of alchemy”. Perhaps the choice to make clear that Dr El Daly’s statement is a quotation actually reinforces the authority of the museum rather than challenges it; it definitely doesn’t acknowledge the fact that the British Museum’s rhetoric in the past is the reason the balance needs to be redressed today. Instead, the museum can pat itself on the back for representation of local knowledge and call it a day.

There were more clumsy attempts at inclusivity in the form of the reactions of children of Rashid to various objects in the exhibition. This was badly done and very patronising. Lacking the context of the full outreach programme – which actually seems to be sensitive and locally grounded – the children’s words were pretty much meaningless. “[It looks like] a cookie!” says Fatma, 12 years old, referring to a cylinder seal of King Pepy I.

Once again, the authority of the British Museum is reinforced. They are the expert, the adult in the room, whilst the people of Egypt are literally infantilised.

It’s worth noting, too, that the children never had access to the actual objects that they were commenting on; they were shown pictures. Obviously, that’s because many of those items are in the hands of the British Museum or other European institutions. Less obviously, at least according to this exhibition, is how or why that happened. Magic, maybe?

Each of the objects is labelled with its original provenance (date, location, material), beneath which is the collection it is sourced from (overwhelmingly the British Museum, with French museums also represented). What’s not shown is how those objects travelled between these two locations. Who found them? Who donated them? Did they go anywhere else before coming to the collection? How many hands have they passed through?

Occasionally, this information is revealed, most prominently with the Rosetta Stone itself. This is because the history of its translation is intrinsically bound with its manner of collection as a war prize. The campaign in Egypt, fought by the French against the Ottoman Empire and the British from 1798 to 1801, forms a satisfying narrative precursor to Jean-François Champollion and Thomas Younge’s later hieroglyph decoding rivalry. Attention is paid to the fact that the stone was discovered, built into a wall, its importance apparently unrecognised and unappreciated until that moment. French General Jacques-François de Menou protested the Stone’s transferral to the British under the Treaty of Alexandria (1801) by arguing that it was as much his as “the linen of his wardrobe or his embroidered saddles”. Finders, keepers, etc., etc.

It perhaps goes without saying that neither party seemed to care what the invaded Egyptians thought of this stripping of antiquities, or even considered them as part of the equation at all. And in this exhibition, the British Museum continues to treat the whole saga as a natural sequence of events. There is no reflection on the process whereby the Stone (or any other artefact) came to join the collection; we are expected to take for granted that in the collection is where they ultimately belong.

This is an exhibition with an abundance of material context. Literally reams of it. The curators could have found a new way to communicate through the object, to reveal the paths of translation through the appropriation of objects under colonialism. Instead, by adopting the omnipotent voice of the institution and only including other perspectives as additional support for its narrative, by obscuring the processes of collecting, it reinforces an Orientalist perspective that continues to work in the Museum’s favour.

I wanted to love Hieroglyphs, because it speaks to a childhood wonder about the ancient world, tapping into my personal nostalgia for watching sand-swept presenters climb through hidden tunnels into mysterious tombs. It’s hard to ignore, though, that the Museum has a huge amount of historical Egyptian objects and never once explains why it has them. That’s a can of worms they are fighting to keep a lid on, but it’s a fight they need to lose. Our cultural discourse would be so much richer and fairer for it. And, as we know from the removal of women from Ramesses II’s king-list, just because you don’t write about it, doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.

Hieroglyphs: unlocking ancient Egypt is showing at the British Museum until 19th February. Tickets are £18 for adults.

For more reading on this subject, try these articles from the Smithsonian Magazine, the Art Newspaper, and this one from Al Jazeera.